This article was initially published on the Inter-American Development Bank’s blog – Ideas que Cuentan, on June 13, 2024.

Between 1960 and 2019, Latin America and the Caribbean grew faster than advanced economies in terms of labor, years of schooling, and physical capital. However, the difference in average annual growth between the two categories of countries was striking: advanced economies grew by 2.6%, compared to 1.8% for Latin America and the Caribbean.

The biggest difference between the two groups of countries—and with emerging Asia, which grew at around 4.5% annually—was productivity, a factor that constitutes the biggest growth challenge for Latin America and the Caribbean. Productivity advanced steadily in advanced and emerging Asian economies at around 1.4% and 2.3% respectively during those six decades. But in Latin America and the Caribbean, it stagnated at 0.06%, with profound negative repercussions for living standards and national wealth.

If productivity were more robust, the region would currently look very different. If it had kept pace with emerging Asia’s productivity, the region’s GDP would have been 3.6 times larger. Furthermore, its per capita GDP would have stood at 90% of the United States’ level, instead of the much lower 25% where it stood in 2019.

These deficiencies point to a major challenge: the region must significantly improve the factors that lead to higher productivity, including education and the allocation of capital. Only then will it be able to unlock its economic potential and significantly reduce its enormous development gap with more prosperous areas.

Lagging in Education

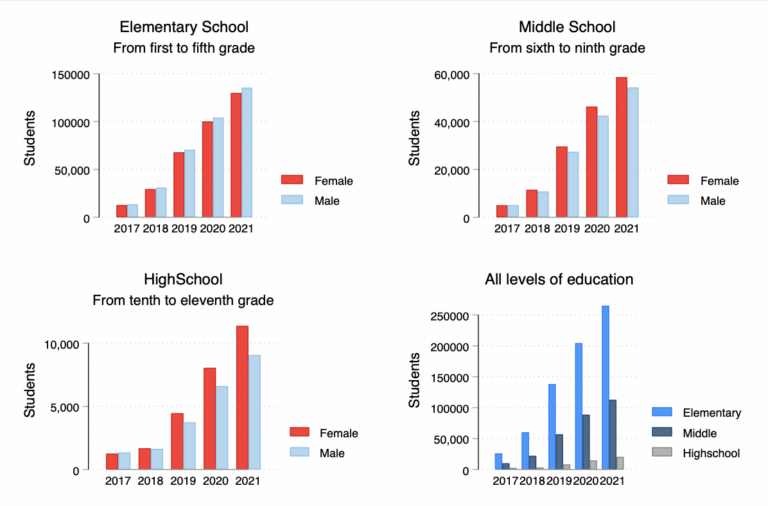

Improving the quality of education is fundamental. As highlighted in the recently published 2024 Macroeconomic Report for Latin America and the Caribbean, the region has substantially increased the average years of education people receive. Countries in the region with higher per capita GDP generally enjoy more years of schooling than their lower-performing counterparts. But quality is a sensitive issue. In the 2022 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), a test that compares the abilities of 15-year-old students worldwide, students in the region were, on average, behind their OECD peers by the equivalent of five years of schooling in mathematics. They also performed worse in reading and science than students from most participating countries.

Inefficient capital allocations also hold back the region. Preferential tax treatment for small businesses and restrictions on the size of larger ones lead to lower production at both the firm and economy-wide levels. High taxes and demanding regulations for formal sector companies, including those related to payroll and dismissal costs, encourage companies to remain informal, smaller, and less productive. And protectionist trade measures, such as tariffs and quotas, shield unproductive domestic industries from international competition and prevent the reallocation of capital to more productive sectors.

Credit markets need to be more competitive and offer cheaper credit. Currently, too many unproductive or established companies have preferential access to credit, while companies with innovative ideas and high growth potential beg for financing. In Brazil alone, the misallocation of credit may have cost the country up to 39% of its GDP, according to a recent paper.

Boosting Productivity to Escape the Middle-Income Trap

In 2016, IDB colleagues published a groundbreaking study to determine which sectors in a given country needed greater investment to increase productivity and help that country jump to a new level of per capita income. According to the study, several countries in the region moved into the upper-middle-income group between 1990 and 2019. But there was still a huge gap between those countries and high-income countries, which focused on the determinants of productivity and the effort required to escape the so-called middle-income trap. Our most recent study builds on that work. It shows that, among many other reforms, countries need to greatly improve the quality of their education, their trade openness, and their tax, regulatory, and credit market regimes. While productivity is essential for prosperity, it can only be achieved with better human capital and pro-competition policies that fight monopolies and market power, leveling the playing field for all companies.