September 23, 2024

Green, How I Desire You Green: Requirements, Capabilities, and Transformations of Tax Administrations in the Face of Environmental and Climate Challenges

By: Juan Pablo Jiménez, Luis Miguel Galindo, Fernando Lorenzo, Andrea Podestá

Tags:

In the coming years, the tax systems of the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean (ALC) will undergo significant changes to address climate and environmental challenges. These tax transformations will require a considerable adaptation effort from Tax Administrations (AATT), which will need to strengthen their technical capacities, supporting governments in the adaptation of tax instruments, efficiently managing new taxes, and generating new information bases that allow for the evaluation of the impact of environmental taxes.

To address the challenges of climate change and promote sustainable development, a new fiscal strategy is essential. This strategy should incorporate appropriate economic incentives and contribute to mobilizing greater resources to finance the investments necessary to meet climate goals. The region, particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, faces the complex challenge of integrating environmental, economic, social, and revenue-raising criteria in the design of fiscal tools, while simultaneously incorporating considerations of political economy, distributional objectives, and addressing the competitive capacity of economies in an increasingly globalized scenario.

In this context, we have recently conducted a study (cite Jiménez, Galindo, Lorenzo y Podestá, 2024) that examined the specific needs of the AATT in the region to address the transition towards a more environmentally friendly model in an efficient, effective, and equitable manner.

The analysis conducted reveals that in the countries of the region, there is room to expand the use of green taxes, that is, those tax modalities whose taxable bases are defined in terms of physical units (or a substitute thereof) that express the magnitude of specific and proven negative impacts on the environment. Therefore, a particularly important feature of environmental taxes is that their taxable bases are related to the negative environmental externality they aim to address, and that the tax rate structure reflects the environmental damage as accurately as possible, thereby contributing to the achievement of certain objectives.

Environmental. Given that the environmental tax aims to internalize a negative externality, it is recommended that the levy be of a specific type, meaning that it is collected based on the quantities produced or consumed of the goods and services that are at the origin of the environmental damage.

Environmental levies can be classified according to their tax base into three groups: energy (generation, distribution, and utilization in its different forms); motor vehicles and transportation; and others (pollution and natural resources).

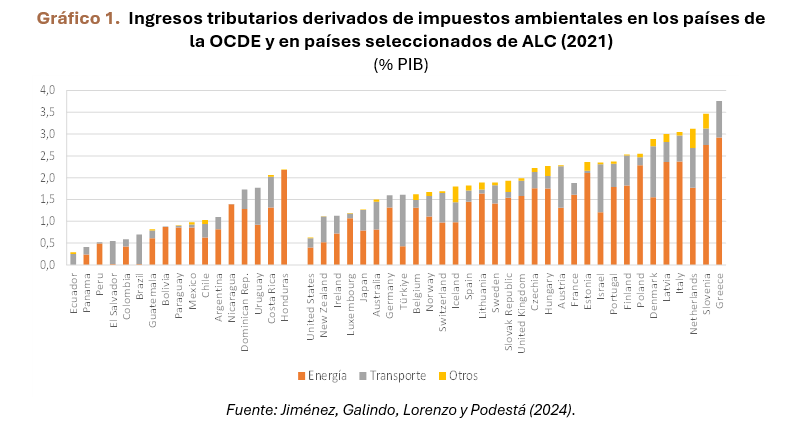

In Latin America and the Caribbean, environment-related taxes are significantly lower, in terms of GDP, than those applied in OCDE countries (Figure 1). Furthermore, the relative importance of these taxes in the countries of the region is highly heterogeneous. The contrast is evident when comparing countries such as the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Costa Rica, or Uruguay, which in 2021 had revenues from environment-related taxes between 1.7% and 2.2%, with other countries such as Ecuador, Panama, Peru, or El Salvador, where this type of tax is very insignificant. Regarding their structure, in general, energy taxes predominate, which mainly include taxes on fossil fuels, carbon taxes, and levies on the production, distribution, and commercialization of electric power.

However, in line with international trends, the countries in the region have witnessed a decline in tax revenues obtained from energy taxes in recent years. The reduction in the relative importance of revenue from these taxes is noticeable when compared to the situation prevailing at the beginning of the 21st century, when a maximum collection had been reached in most countries (Figure 2). Additionally, the existence in several ALC countries of a substantial amount of subsidies for energy products -including fuels- represents a significant challenge in terms of environmental policy.

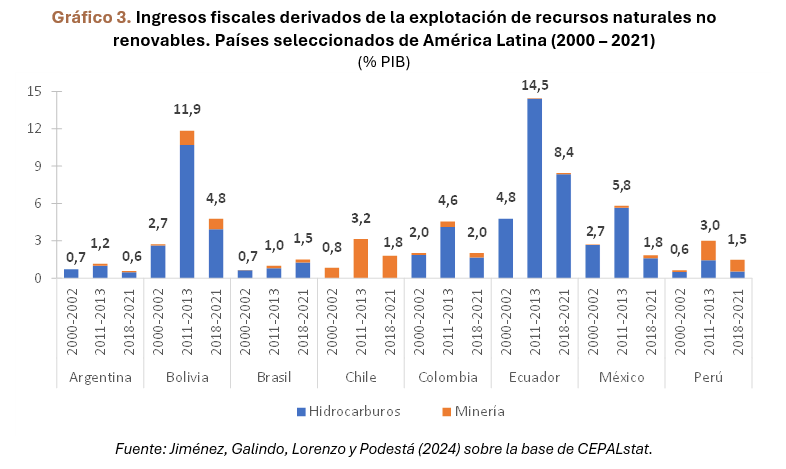

On the other hand, while the nomenclatures usually used by international organizations (OECD, European Union) to classify environmental taxes include levies on natural resources, those taxes that burden the exploitation and extractive production are not usually considered environmental taxes. Although the dominant objective of taxation in these cases is the appropriation of extractive rent and the collection of fiscal revenue, many of these levies, such as revenues from royalties, have a significant -and often unwanted- environmental impact through their effects on production. Despite the fact that they are not strictly considered green taxes, their high environmental impact and their fiscal importance mean that they potentially deserve to be considered as tools for an environmental tax reform (Figure 3).

Beyond the limited quantitative relevance of green taxation in ALC, the poor quality in the design of many taxes is concerning. Frequently, these taxes exclude significant polluting sectors and activities; while the applied tax rates may not adequately reflect environmental impacts, thus frustrating the objective that justifies this type of tax modality. It is also common that, with the aim of improving environmental reputation (“green washing”), certain taxes are labeled as environmental, even though environmental considerations have not been explicitly incorporated into their design. Furthermore, there is excessive administrative complexity and an uneven and uncoordinated proliferation of taxes at different levels of government, where some tax bases often have little connection with the environmental problems they are intended to address.

To support the design work of an environmental tax system that meets its objectives, the Environmental Authorities (AATT) require information on the price and income elasticities of demand for the good or service in question, as well as on the main cross-price elasticities of related goods (substitutes or complements) that serve to estimate the demand response to tax changes and the effects on fiscal revenue.

Developing an agenda that allows progress in the redesign of tax systems with environmental considerations requires having a robust capacity-building program for personnel, with targeted training experiences led by both technical professionals from the tax administrations themselves and external experts. It is important that officials have a clear guide for the preparation of analytical studies and that they receive training in the design and use of tools that allow them to understand the effects of green taxation in different climate scenarios.

Training programs should cover the various aspects that link the process of deep decarbonization of the economy with the use of fiscal and tax tools that contribute to defining a new system of economic incentives aimed at producing a structural change in current consumption patterns and in the forms of production that are at the root of climate change. Thus, through the training programs and the accumulated experience in the development of this type of tax tool, officials could acquire skills to monitor a wide range of aspects related to climate change.

On the other hand, to mitigate the impact of environmental taxes on income distribution, it is crucial to consider the role of compensation mechanisms. These can materialize through various instruments, such as tax expenditures (differentiated rates, tax credits, exemptions, etc. for more vulnerable sectors), subsidies for the acquisition of equipment and facilities, and targeted cash transfers. It is essential that compensation strategies are carefully and transparently designed and implemented, ensuring an equitable distribution of the benefits and costs associated with green taxes. At the same time, it is fundamental that the compensations do not counteract the environmental improvement achieved by green taxes or reduce the effectiveness in correcting negative environmental externalities

A recommendable practice is to allocate a portion of the revenue collected from green taxes to finance activities related to environmental preservation, as well as to use a share of these fiscal resources to implement targeted distributive compensations, such as subsidies directed towards low-income groups or investments in affected communities. The Territorial Administrative Entities (AATT) can allocate part of the funds raised to education and training programs, especially aimed at small businesses, to facilitate adaptation to new environmental policies and improve the efficiency of their productive practices.

It is important that continuous monitoring systems are established to evaluate the distributional impacts of green taxes, in order to adjust tax policies and improve the design of compensation mechanisms. Furthermore, it is crucial to foster dialogue and citizen participation in decision-making regarding environmental taxes and compensatory measures, which can contribute to designing more equitable and accepted solutions for taxpayers. Similarly, to effectively address distributional impacts, it is essential to promote cooperation among various government bodies, civil society, and the private sector.

Another area where the role of Tax Administrations (AATT) is relevant is in the preparation of studies on tax expenditures, as they constitute a significant input for conducting cost-benefit analyses regarding these preferential tax treatments. To this end, it is necessary to focus not only on tax expenditures with a positive impact in terms of climate action, but also to address the effects of tax expenditures with negative environmental repercussions, including their effects on production and income distribution.

To meet new challenges, the AATT (Tax Administrations) must advance in the adoption of new practices, in the strengthening of the technical capacities of their personnel, and in the collection of detailed and updated information that allows for the evaluation of the impacts of green taxation in the economic, social, and environmental spheres.

It is important to highlight that, although specific taxes can be useful for addressing negative environmental externalities, the presence of inelastic demand limits the effectiveness of applying taxes to increase prices and fully control them. Therefore, it is necessary to complement green taxation with new regulations, accompanied by a greater effort of public investment in sustainable infrastructure, and to promote a revision (reduction or elimination) of subsidies for fossil fuel consumption.

En definitiva, las AATT deberán acompañar los esfuerzos de adecuación de los sistemas tributarios, aportando una perspectiva integral y transversal, y asumiendo los desafíos que implica la implementación de impuestos ambientales que requieren un desarrollo técnico cuidadoso y una evaluación detallada caso por caso.