This blog post originates from a Master’s thesis in Economics at the Universidad del Rosario, supervised by Professor Darwin Cortés, renowned for his scientific rigor. We thank Vox.LACEA for providing this platform to our students.

The Colombian labor market is highly informal, leading to nearly half of the employed population earning income from profits and salaries below the current legal minimum wage. Additionally, figures from the National Administrative Department of Statistics -DANE- show double-digit unemployment rates since 2018, a figure that worsens when we focus on young people between 15 and 28 years old, as they face an average unemployment rate 1.6 times higher than the general population.

The prospects for Colombian workers are not very good, and neither are those for employers, as the Manpower Group’s 2022 talent shortage survey indicates that 3 out of 4 employers have difficulty finding the talent they need, a situation that has been worsening year after year. High unemployment rates and significant difficulties in finding talent are a sign that, in the Colombian labor market, supply and demand are poorly matched.

In our study “Finding Formal Work in Colombia: A Question of Skills?” conducted with Darwin Cortés, we analyze the relevance of higher education in training suitable technicians, technologists, and professionals for the labor market. In particular, we quantify the effect of the skills gap between educational supply and labor demand on the likelihood that a recent higher education graduate contributes to social security, that is, formally enters the labor market.

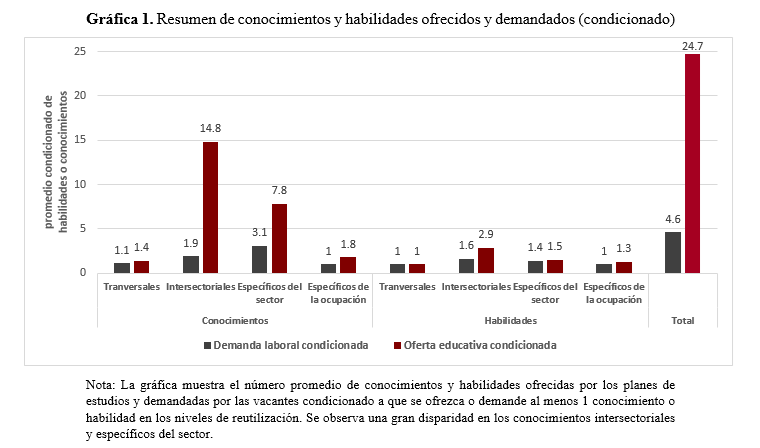

Although young people who manage to access higher education do so with the expectation of learning a specific occupation and being able to find work related to their studies, when analyzing 3,692 curricula of technical, technological, and professional programs from 13 capital cities, and comparing them with job vacancies published on the Public Employment Service, we found that: 1) higher education teaches 5 times more knowledge and skills than employers demand on average, but, 2) while employers seek workers with specific knowledge of the sectors, higher education institutions primarily teach young people intersectoral knowledge, that is, more generic knowledge than employers require. This result helps to understand why employers report difficulties in finding the talent they need in the Colombian labor market.

When specifically comparing the curricula of technical, technological, and professional programs with job vacancies in the related field of study, that is, with vacancies that a graduate of a given program could apply for, we found that on average more than 80% of the knowledge or skills requested in the vacancies are not taught in higher education programs.

Undoubtedly, not having the knowledge and skills that employers require makes it more difficult for young people to find formal work. In fact, the skills gap alone between what is taught in higher education and what employers require reduces the probability of recent graduates finding formal work (where they contribute to health and pension) by 12 to 23 percentage points, to which are added other barriers such as the lack of work experience of young people, which limits the vacancies they can initially aspire to.

Understanding that there is a significant difference between what young people study and what the productive sector requires opens up a series of debates that we must address as a country. How can higher education institutions (HEIs) become more aligned with the productive sector? The current Minister of Education, Alejandro Gaviria, has identified that the current quality assurance system for higher education makes it difficult for HEIs to update their curricula, thus creating a barrier for HEIs to align with the productive sector. However, we must go further. What innovation is relevant for each program or area of study? Making the high-quality accreditation system more flexible will not generate alignment between HEIs and the productive sector if we do not know what we need to align. Therefore, it is also required that, from the ministry or through private initiative, changes in the demand for knowledge and skills by employers are constantly monitored so that HEIs have appropriate information to make their curricular adjustments.

References:

Manpower Group (2022). Talent Shortage in Colombia 2022. Retrieved from: https://manpowergroupcolombia.co/cases/escasez-de-talento-en-colombia-2022/

DANE (2021). Labor Market Information. https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/mercado-laboral/empleo-y-desempleo